“We achieved peace by sacrificing an enormous amount of blood, sweat and tears of our people. We only hope that for Japan and the people, we never go through such a horrible day. We never should start a war. This is a message from someone who went through a war.” -Tatsuya Nakadai

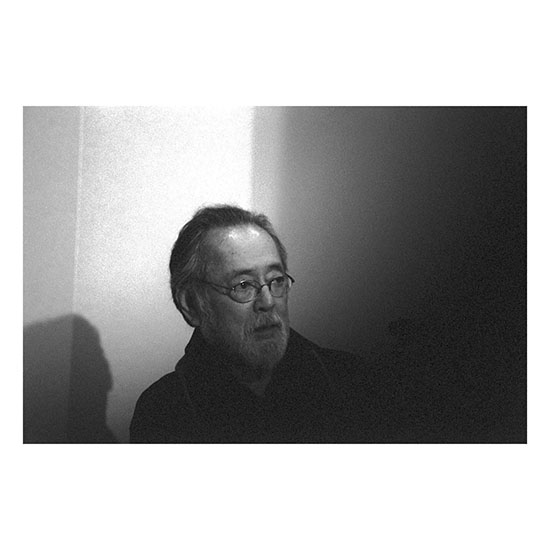

I received sad news that Tatsuya Nakadai passed away on November 8th at the age of 92. Mr. Nakadai was one of Japan’s greatest and internationally acclaimed actors. In 2014, I photographed a portrait of him for a magazine and later found out that he was a survivor of the Tokyo firebombings during the Second World War. I asked him if I could photograph a portrait of him for my From Above project. The portrait was different from the portrait I previously photographed that accompanied an article about his storied career. For the From Above project, I asked him to remember his experiences as a kid during the war, and I took a few steps back with my camera.

Mr. Nakadai’s portrait has been shown in several From Above exhibitions. Some visitors are surprised to learn that he experienced the war. I’ve always felt that because Mr. Nakadai was famous, people thought that he would not speak about the experiences he endured during the war.

I’m proud of the brief time I spent listening to Mr. Nakadai. After I sent him the portraits, his manager, Ms. Wakao wrote to me. The message revealed that Nakadai-san posted all of them on the wall of Mumei-juku studio. He wished the best for my exhibitions, and although he was not a hibakusha, he survived the war and wanted to convey a message of empathy. Ms. Wakao also wrote that my portraits were powerful and different from other photos of Nakadai-san.

Nakadai-san was steadfastly anti-war. I’ll end with his words.

“After March 10th, the air raids continued in downtown Tokyo and my family house in Yamanote was blown away by a bomb blast on May 25th. It broke windows, and glass pieces poured on me like a waterfall. In a cloud of dirt, I was running away leading my neighbor’s little girl, but after a while, I realized I was holding only her hand. Her body was blown away by the bomb.

My mother and I wandered in hell-like streets the next morning. Burnt bodies were everywhere. They made strange sounds as they were still burning. Many bodies that I saw were holding both hands up in the air and mouths were wide open as if they were screaming.”