…8:11pm… …Stonewall Protests…

…8:11pm… …Stonewall Protests…

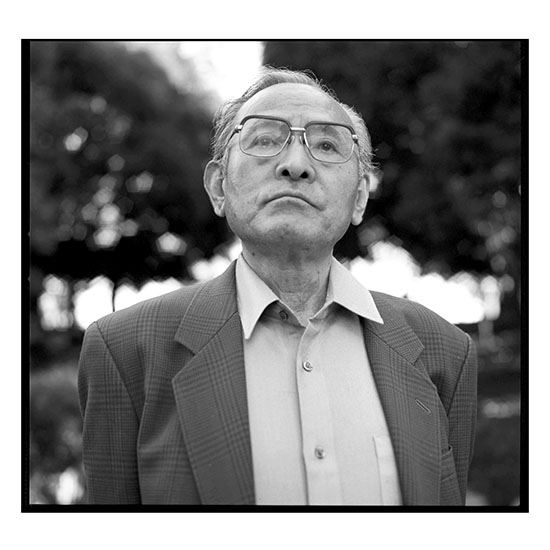

I received the sad news that Mr. Matashichi Oishi passed away on March 7th. Mr. Oishi was a former crew member of the Daigo Fukuryu-Maru (Lucky Dragon 5), tuna fishing boat that was exposed to radiation by an unannounced secret hydrogen bomb nuclear test at the Bikini Atoll on March 1st, 1954. They were fishing 160km away from the hypocenter. The bomb was 1,000 times more powerful than the atomic bomb detonated in Hiroshima. It contained 270 different kinds of radioactive materials.

Mr. Oishi saw a strong flash of light. An orange color soaked the sky. After 7 minutes they heard horrific rumbling. Strangely, the sea surface stayed calm. Frightened, they decided to return home. Soon after “ashes of death”(nuclear fallout) started falling, covering the boat like snow. They had no idea what it was, some licked the flakes. The flakes of ash didn’t melt, felt like sand and burned their skin. They removed the fishing nets and long fishing lines while the radioactive ashes fell.

After a 2 week journey, they arrived at Yaizu harbor. All of them already began to suffer from acute radiation diseases such as dizziness, loss of appetite, gum bleeding, diarrhea, vomiting, and hair loss. But they still didn’t know what they were exposed to.

A newspaper released the news about the nuclear test. It caused a panic in Japan. “Poisoned fishermen brought back poisoned tuna.” Even rain contaminated with radioactivity fell over Japan and other countries in the Pacific Ocean.

The panic created an anti-nuclear movement and encouraged Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bomb Survivors to speak about their experiences. Nearly 10 years after the bombings in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, this was the first public discussion about nuclear weapons in Japan.

During the American Occupation, news about the atomic bombings in Hiroshima and Nagasaki was censored. The American government allowed no public discussion or newspaper articles in Japan to be written about the bombings. Because of the censorship the Japanese public, outside of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, were largely unaware about the effects of radioactivity.

The Lucky Dragon 5 event was covered up in negotiations between the US and Japanese governments. The boat was painted over and dumped in a landfill in Tokyo. The ill fishermen were abandoned and outcast socially. Their lives changed completely. They didn’t have visible burn or scar but inside their bodies were radioactively contaminated. All battled various types of cancers throughout their lives. The first member of the crew died a half year later. More than half of the crew has died. All of them died from liver cancer.

Mr. Oishi suffered from varied aftereffects; including liver cancer and social discrimination. The company and government have claimed no responsibility for his health care bills even though he was exposed while working.

After 30 years of silence, he started to speak about his experiences. He is one of only two voices out of 23 Lucky Dragon crew members to speak. 856 boats, containing 17,000 Japanese fishermen, were present in the marine area the day of the nuclear test at Bikini Atoll. None of the others have chosen to speak or release their medical records.

Mr. Oishi was photographed at the location where the Lucky Dragon 5 was found. The discarded boat was discovered in 1967. The boat has since been persevered and a museum has been built around it.

It was an honor to photograph Mr. Oishi. I will always admire his bravery for speaking the truth. He’ll always be my friend.

“I poured the water I was carrying, over my head then poured the water into my hand and put my hand to my lips. We helped each other and endured the suffocation. Gradually, the burning heat had gone.”

-Hiroo Fujima, Tokyo firebombing survivor

On the night of March 10th, 1945 Tokyo was pummeled into ash. The men, women and children in one of the world’s largest cities, crumbled under a calculated reign of fire. More civilians died that night in Tokyo than both atomic bombings combined.

This portrait is a part of my From Above project which featured portraits of atomic bomb and firebombing survivors from WWII. My limited edition book is available at https://www.photoeye.com/bookstore/citation.cfm?catalog=I1040&i=&i2=

A small selection of From Above is being exhibited at Gallery èf in Tokyo to commemorate the people who perished in the destruction of Tokyo. The exhibition is open until March 10th.

“In November 1944, as the eastern front began to move west, my mother, brother (age 3) and I ( age 11) were then taken by open cattle car to Dresden. The weather was frigid. With about 500 others we were forced to work in a cigarette factory at Schandauerstraße 68 which had been converted to an ammunition factory. I worked twelve hours everyday on a milling machine cutting metal that was made into ammunition encasements for the Wehrmarcht. If our daily quotas weren’t met we had to work longer hours but we made sure not to exceed the quotas as a sudell form of resistance. Any sabotage would have been dealt with harshly.

We were never allowed to leave the factory. On the afternoon of February 13th, just hours before Dresden was firebombed, an SS officer declared that my younger brother was to be executed the next day because he was too young to work and was “a useless eater.” That night Dresden was bombed. The workers and guards sat in the large cellar all night. The workers who were sick stayed above in the factory dormitories. The factory was hit by incendiary bombs and the upper floors of the building burned. Only those in the cellar survived. My nerves broke down during the bombings. Everytime I heard a plane I went diarrhea. For a while after I was extremely traumatized and stuttered while I spoke.

When we left the cellar in the morning, white ash was everywhere. There were a lot of dead bodies, buildings were damaged, trees were on fire and even the streets had melted. I was ordered to clean up the rubble that was blocking streets and railway tracks while adults had to carry corpses.

In April we were put on a forced death march south west because the SS were fearful of the advancing Red Army. We were given no food and many of us were emaciated. At one point we were attacked by an Allied plane. The SS officers, who were guarding us, ordered us to jump into a ditch on the side of the road. After the plane flew away my mother, brother and I stayed on the ground and didn’t move while the SS officers quickly forced the others to continue. In their rush to flee they must have thought we were dead. After they left I went to a farmer in Pilsen, who gave me food. The first ten years after the war we didn’t speak about it.

The first time I came back to Dresden was in 1955 to meet with the others who had been forced to work in the factory. During the time of the GDR, I wrote to East German officials about my experiences at the factory but they denied that such a factory existed. After reunification a plaque was placed outside the factory saying that a lot of people were forced to work there during the Second World War.”

-Michal Salomonovič, Dresden firebombing survivor

Mr. Salomonovič is photographed outside the factory at Schandauerstraße 68. His family was originally from Ostrava, Czech Republic and were deported by the Nazis from Prague when he was 8 years old to Lodz ghetto then to several concentration camps before being sent to Dresden to work as a forced laborer.On February 13th, 1945 the baroque city of Dresden, Germany was firebombed into cinder by the British Royal Air Force and the United States Army Air Force. The attack was divided into three bombing raids dropping over 4,500 tons of high explosives, including incendiary bombs, onto the city known as “Florence on the Elbe.”

This portrait is a part of my From Above project which featured portraits of atomic bomb and firebombing survivors from WWII. My limited edition book is available at https://www.photoeye.com/bookstore/citation.cfm?catalog=I1040&i=&i2=

“It’s hard to put into words, it left a mark on our lives”

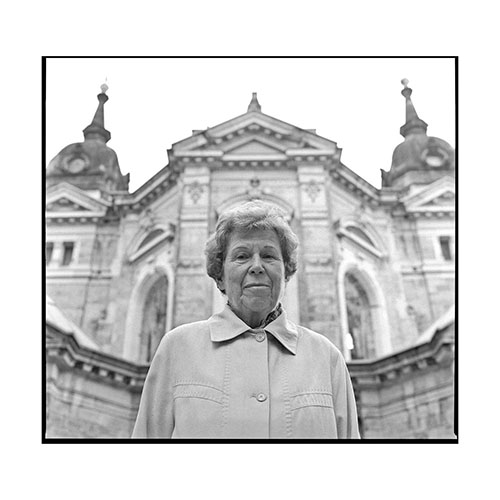

-Anita John, Dresden firebombing survivor

Anita John was twelve years old at the time of fire bombings. She lived with her family in Dresden-Johannstadt. Her family took shelter in a cellar with the other residents in the building. They did not evacuate the area and were caught unaware by the second attack. Fire was raging outside the steel cellar door. It was producing extremely high temperatures inside the cellar. Oxygen was quickly becoming scarce.

Anita and her family lay down on the floor together with the others. She covered her mouth with a damp bathrobe that helped her to breathe whilst smoke filled the cellar. At first they all survived the attacks, until the immense heat from the raging firestorm consumed all the oxygen inside the cellar. All, but one, died of smoke inhalation.

Sixteen hours later, a soldier looking through the ruins for his wife broke a small window accessible from the street. Oxygen came into the bunker. Only Anita woke up amongst the dead. Her parent’s bodies lay silent, close by on the floor. The soldier saw Anita’s body move and took her to the aid station. The water in the damp bathrobe had allowed just enough oxygen to keep Anita breathing.

The last memory Anita has of her parents is telling her father “I want to lie here”. Her mother responded, “Then let’s stay”. Anita grew up with her uncle.

Mrs. John was one of the few survivors I met who continued to live close to where she lived at the time of the bombings. I believed in some way it was a way for her to still be close to her parents. She is photographed in front of the destroyed Trinitatiskirche, where her parents were married and she was baptized.

On February 13th, 1945 the baroque city of Dresden, Germany was firebombed into cinder by the British Royal Air Force and the United States Army Air Force. The attack was divided into three bombing raids dropping over 4,500 tons of high explosives, including incendiary bombs, onto the city known as “Florence on the Elbe.”

This portrait is a part of my From Above project which featured portraits of atomic bomb and firebombing survivors from WWII. My limited edition book is available at https://www.photoeye.com/bookstore/citation.cfm?catalog=I1040&i=&i2=

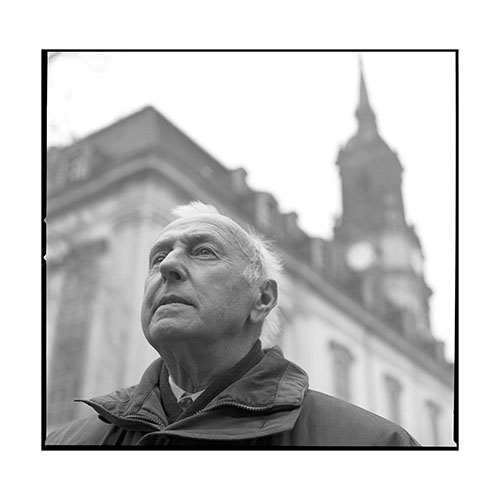

“When we left the cellar our house was on fire, all the windows were shattered and we had to run. We lived on the fourth floor of a house in a poor area near the center of the city.

The worst thing wasn’t that our house was on fire – but my mother was Jewish. My father was not Jewish. So Hitler said I was mixed. Which is not true because if a mother is Jewish then the children are also Jewish. Before I was born my mother converted to Christianity but the authorities didn’t recognize this. We were a Christian family. I sang in the church choir and played with the Reverend’s kids.

In Dresden the Jewish population had been systematically persecuted, especially during Kristallnacht when 700 Polish Jews were expelled. In 1942, they wanted Dresden to be “Judenfrei”, free of the Jewish population. The remaining Jews were forced to wear a star on their clothing and work in the Zeiss Ikon armament factory which produced time fuses for the navy. They were evicted from their homes and forced to live in hastily built wooden barracks located in a camp called Judenlager Hellerberg on the outskirts of Dresden. In March 1943, they were deported to death camps. Of the 250 deported, there are 10 known survivors. It’s always easier to give the statistics but during all these deportations, I lost family and friends.

The day before Dresden was attacked the 17 remaining Jewish families received an order that they were required to report on February 16th for deportation to Theresienstadt. I still have a copy of the letter which is very rare. I only know one book that was published in the GDR times where one of these letters was printed. The journalists were courageous to have published it.”

-Norbert Schlechte, Dresden firebombing survivor

On February 13th, 1945 the baroque city of Dresden, Germany was firebombed into cinder by the British Royal Air Force and the United States Army Air Force. The attack was divided into three bombing raids dropping over 4,500 tons of high explosives, including incendiary bombs, onto the city known as “Florence on the Elbe.”

This portrait is a part of my From Above project which featured portraits of atomic bomb and firebombing survivors from WWII. My limited edition book is available at https://www.photoeye.com/bookstore/citation.cfm?catalog=I1040&i=&i2=

..January 2021.. ..Nagasaki..

Yesterday the Asahi newspaper in Nagasaki included my opinion about the Treaty Banning Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) which was enacted as international law on January 22nd. A big thank you to Mizuki Enomoto for asking me to contribute to her article.

I began photographing atomic bomb survivors (hibakusha) in 2008 and will continue to do so until the last voice goes silent. In 2011 these portraits were published as a book, From Above. Everyday I think about the people I met in Nagasaki and Hiroshima. Most have passed but their memory lives on when the treaty banning nuclear weapons arrives.

“When I sit to write my recollections of that time, I have to brace myself to confront my memories of Hiroshima. It is exceedingly painful to do this because I become overwhelmed by my memories of grotesque and massive destruction and death.”

-Setsuko Thurlow, Hiroshima atomic bomb survivor

On January 22nd the Treaty Banning Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) will be enacted as international law. I began photographing Mrs. Thurlow in 2011. From the moment we met her determination to fight for the abolition of nuclear weapons was evident. She was 13 years old when the atomic bomb destroyed Hiroshima. Mrs. Thurlow was a prominent advocate of the treaty that will ban nuclear weapons. She has waited almost all her life for this moment.

Everyday I think about the survivors I met in Nagasaki and Hiroshima. Most have passed but their memory lives on when the treaty banning nuclear weapons arrives.